|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

(A wise man, a reporter, and his PHOTOBOOK/legacy, by Tiziano Dal Farra. Here the text-only content of)

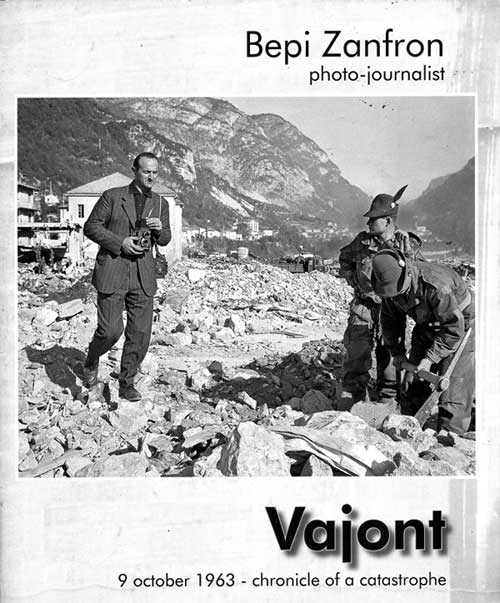

VAJONT, 9 October 1963Chronichle of a catastrophe

At 22.39 on 9 October 1963, after several warning signs, a mass of rock almost two kilometres and five hundred metres wide sheered away from the slopes of Mount Toc; an estimated two hundred and sixty million cubic metres of rock travelling at a speed of 80/90 kilometers per hour fell into the Vajont reservoir, which at that moment was at a level of 700.42, or twenty five metres below the maximum level of the highest double arch dam at it's time in the world.

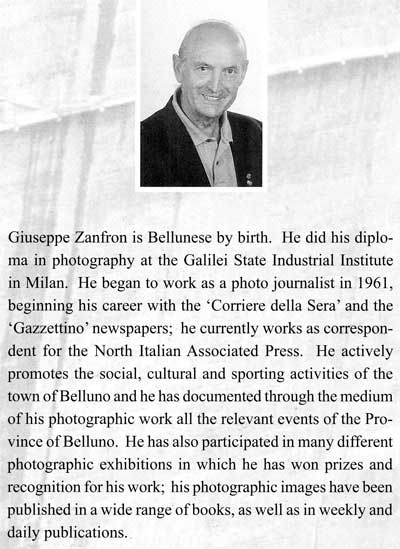

Vajont, 9 October 1963By Sergio SommacalLandslide of Longarone from the direction of the Vajont, perhaps because of a burst pipe. "Three or four dead. No more known at this stage." On your way, Bepi. You will need to move more quickly if you are to keep up with the sirens of the fire engines that shatter the silence of a tranquil autumn evening dedicated to watching football on tv. Three or four dead, they say. Who knows what has happened. Hurry up, get a move on. Haven't you always wanted to be a photojournalist? Then put your foot down. News stories we well know require a dedication that means foregoing the comfort of social relationships and ordinary routines of life. 183 This evening is no exception. "I was in the Piazza del Martiri, going home after my German lesson. Suddenly all the lights went out and Belluno was plunged into darkness. A quick dash into a shop, a phone call to the fire brigade, the first fragments of information: I was off in a flash." News photographer by profession: impossible to move one step without a camera in one's hand and rolls of film in one's bag. One bag full of equipment is always left ready in the studio, another in the car which is always full of petrol: one can never even count on being able to finish a quiet dinner at home with the family. One has to be contactable every day at every hour, whatever the weather. Unquestioningly available, always. It's a dog life, but it was the one he chose. A country boy through and through from Villa di Villa (Mel, BL) Bepi Zanfron was born the second youngest of six brothers in 1932. His first infant memories are of Val d'Arch, in the comfortable world of the left bank of the Piave river, which flows between the Bellunese area and the Venetian plain. Then there were the last dreadful war years at Paludi d'Alpago, after his family had dispersed: the black bread, the nightmare of the bombings. And finally there was the move to the haven of Visome, just outside Belluno. Life was about home and countryside; there were few schools, and few opportunites, but he was brimming over with energy, interests, curiosity and initiative. There he spent the days of his adolescence, involved in acting and in competitive sports. There was skiing, gymnastics, track events, cycling; there were the confrontations with one's rivals and the recognition of one's own limitations. Above all he excelled when he had to depend on his own efforts: it means something to have won the 'Gran Premio della Montagnà in one of the Piave cycle races, competing in the colours of the Belluno Veloce Club team. Then came military service: the Italian alpine troops at Bassano, in the Tolmezzo battalion where new recruits went to be broken in. The first camera was bought with money sent from home to boost one's morale during the months in uniform. The effect was as instant and as galvanising as a stroke of lightening. He contemplated no other option after demobilisation: on his return to Belluno contact was made with a modest studio in the Viale Fantuzzi where an elderly man worked as a particularly talented portrait photographer. Bepi was soon out on his bike collecting faded passport photographs from the houses in Valbelluna for Mr. Furlan, his employer, to enlarge and retouch. Colour photography was still a long way off; faces and backgrounds came to life under his deft touch with excellent results and one could say that they were unique works of art. The work was good and Bepi became more and more passionate about it, throwing himself into it and learning constantly, so much so that when a year later his teacher decided to go back to his own part of the country at Oderzo, he proposed that his young assistant take over the studio. This was in 1954 when Zanfron was twenty two years old and it was not at all easy to find money and people to act as guarantors. He succeeded in doing this, and so began his adventure. From this point on the help of his younger sister, Silvia, became indispensable: she was responsible for the shop while he concentrated on taking photographs and perfecting his camerawork and knowledge of materials. This quickly led to his diploma in photography at the Galileo Institute in Milan, and the first commissions that really counted. In 1961 began a regular working relationship with Il Gazzettino, and in the same year came his debut with the Corriere della Sera; in 1962 came the post of correspondent with the Associated Press of Northern Italy.

Just before reaching Fortogna it is possible to catch a glimpse of the Piave river: it seems unnaturally white; there are uprooted trees and even girders. Shortly after this the road disappears. The journey has to continue on feet: a moonless night, bag slung across the shoulders, torch in hand as he moves towards a world that is no longer there. At the bend of the Faè there is the first indication of the enormity of the catastrophe: firemen and traffic police are pulling the injured from the wreckage. There is one dead woman, and then they find another. "I immediately moved to help them, but we had no equipment; no one had expected to find the apocalypse! We were digging with our bare hands." The Protti chapel has disappeared, the houses have been demolished. "I automatically shot some photographs." There was no time to plan or set them up properly.

More rescue workers arrive, and Zanfron begins to walk on.

The highway bridge over the Maè has become a solid impassable wall of wood and rubble. Everywhere you flash the small rounded beam of the torch there are dead and more dead, lifeless and naked corpses. At Pirago only a steeple and a house are visible: nothing else remains. "Here, only at this point, did I really begin to realise what had happened." The light of a lamp cuts through the darkness: it is a friend, Ado De Col, a voluntary fireman who is looking for members of his family. Who knows where they will have ended up. "We wandered around together amongst the rubble, hoping we would find someone still alive; then we tried to think things through logically." These are the words that Zanfron uses: 'we tried to think things through logically'. What he in fact means is that they fell to sharing their anxiety and bewilderment on the night when death came to the mountains above the desert. The moon comes out over the Vajont ravine, but it is only likely to be there for half an hour. "Let's go upwards from Pirago towards the dam. We need to understand whether it has burst; all we can see is a great black mound, a mountain, where we should see the lake." Everywhere there is confusion and tension as well as fear; there are distant sounds, suffocated cries. The attention moves down to Longarone while the darkness begins to come to life with voices and lights. But where is Longarone? It is midnight: only a little while ago it was still there. Now there are groans, while groups of desperate people wander into the void and scratch at the earth with their bloodied hands, on and on without pausing. There must be people under the girders and the rubble who are still breathing, who are still holding on desperately at the margins of the terrible no man's land into which they have been hurled.

Bepi keeps shooting pictures, doing his job: but where is the torch? He gave it to someone to hold to provide some light while he was trying to release a child buried under the rubble. That person then went away and left him in the darkness. A news photographer does not allow himself to be overcome by emotion, this is not the moment for tears. The hours keep on passing: civil and military rescue workers arrive in force, along with ambulances and searchlights. A crater has appeared on the banks of the Piave, a whole community has been annihilated. In its place are lines as though of ants, digging, pulling things out of the rubble, transporting what had been found, as far as the eye can see across the scree. The power of the memory was no help at all to the emigrants who later returned from Europe, alerted by the news on the radio, as they looked out across the barren land of the roads from Zoldo and from Cadore. Where was the piazza - here or there? And the post office? And the bank? And the house in which they used to live? "At 6.30 I returned to Fortogna, found my car and set off for Belluno airport. I had to find a helicopter at all costs." The driving need now is to see from the sky the dead crag of the Toc, the dam, and what remains of the villages, so as to understand what had happened and to help others to understand. Some helicopters have already arrived. "There was a little one, with three people standing beside it. I asked if they could take me to see the landslide; they wanted to know who I was. I explained that I was a photographer who had spent the whole night at Longarone, and that I needed to take some aerial pictures. They discussed this amongst themselves then agreed to make the helicopter available, provided that I took some photographs for them too. I agreed." They are civil servants who are more interested in the fact that the dam has held than in anything else. But Bepi is much more interested in photographing the landslide, which is still settling into place, displacing water and sending out vapours, as well as in what remains of the villages. Once we are up in the air there is a risk of disagreement until I take the initiative: "It will be up to me to tell the pilot where to go, otherwise we will go back down again." The civil servant acquiesces. Three times they go down with their hearts in their mouths to the great black mound, landing on the slopes of the Toc just upstream of the dam. Then Bepi goes immediately to his darkroom to prepare for the newsroom (or perhaps for history?) the films he has taken of the night and the morning after. The afternoon is taken up with more flying, to see Longarone, Castellavazzo, Erto and Casso. The flank of the mountain is scarred as if by monstrous nailmarks; the valley is blocked by the suffocating mass thrown across it; there is an eerie lack of life where before there were families and industrious activity. In its place are the desperate embraces of the survivors as they stand amongst the devastation. "So many memories in those moments: the friends I would never see again, the events both sad and happy of so many years, the small villages which had disappeared forever."

Right from the beginning there had been a particular rapport between the young Bepi in his studio and the place up here in the mountains, while the huge dam was being constructed with its three hundred and sixty thousand cubic metres of

concrete, promising a huge lake of almost one hundred and seventy cubic metres, which would provide a tourist attraction. From the religious fest to the ice cream show, from sporting events to high points in the world of art, from the

minutiae of everyday news to painstaking representations of the environment, Bepi recorded everything with eager curiosity and involvement. This turns out to be extremely difficult as one begins to think of Tina Merlin, Armando Gervasoni, Giancarlo Graziosi and of the journalistic pursuit after the truth that would not allow things to rest; one thinks also of the cracks in the streets and of the trees bent in two, and one realizes that nothing counts any more now that it has happened. The lorries have begun to unload the first coffins: who knows how many journeys they will need to make. Worst of all is fulfilling the request of the police to photograph all the dead who have been laid out together along the Piave between the bridges, the Ponte nelle Alpi and the Ponte di San Felice. It has to be done, otherwise once they have been buried there is no way of identifying the corpses. This task will take weeks, even months. There are almost four hundred ghastly portraits to be taken. The years following the disaster might provide many opportunities to document floods, attacks, and earthquakes, but nothing will approach the horror of Vajont. For this reason several decades after the event this photographic record is offered to the public: it documents the immediacy of the experiences and provides a mosaic of the situations before, during and after the event. The photographs are the working documents of a photojournalist who from the fifties had borne witness to the many happenings in the province. The book presents images of life and of death, some of which are already familiar, while others are being shown for the first time. They are all aspects of a lost world, of a tragedy which had been predicted, but also of life begun again. As Dino Buzzati would say "at exactly the appropriate moment" Bepi Zanfron was there, in order to preserve everything that had happened in the collective memory. Encouraged by a group of friends, I have decided to bring together some photographic memories of the areas affected by the Vajont catastrophe. The selection of material was not at all easy; I have chosen to focus on human and environmental aspects of the disaster in order to remember people and places before, during and after the event. I have not attached captions or comments to all of the pictures; for some of them any kind of explanation would be superfluous.

Bepi Zanfron: the Vajont and his workBy Agostino Perale

While the photography of Bepi Zanfron presents the images of death and disaster, his intention goes beyond the simple representation of reality. As he well knew, images themselves are meaningful and open up the way to hope and to new life. He knew the importance of the past in creating meaning in the present, to enable us to learn from past mistakes; and to ensure that such disasters will not happen

again.

He begins his record by presenting panoramic views of the valleys before 1963: these photographs were used at the trial in L'Aquila to demonstrate the plans for the dam, and its possible dangers.

The photographs go on to document the cruel truth of the rescue operation, the injured, the dead, the survivors who have lost everything, whose grief and shock are too deep for tears: the woman leaning on her arm, the parish priest looking through his mud-covered registers. Then there is the record of the reconstruction: streets, railways, factories, apartment blocks, and a new church with a simple wooden cross standing guard over the many little white crosses which mark the graves of those who died. The Pope, dressed in white, dispenses comfort; a couple place flowers on a small grave. In the end there is hope for the future, and that new life will fill the void left by the disaster created by man's own lack of heed for his environment - and a belief that this page of history will not have been written in vain.

The Past1- Longarone: an old postcard picture 2- Longarone: aerial view 3- View of Longarone looking towards the Vajont, before the construction of the dam. In the background one can see the hamlet of Vajont and the paper mill on the bank just above the Piave river 4- Opening an art exhibition 5- Longarone church, destroyed by the wave from the Vajont 6- The new Longarone church, designed by the architect Giovanni Michelucci and inaugurated on 9 October, 1977 7- The centre of Longarone, and Castellavazzo in the background 8- Panoramic view of Pirago and the river Maè 9- Panoramic view of Pirago and Longarone, showing the wide bank of the Piave river; in the background one can see Castellavazzo 10- Longarone seen towards the Maè valley; in the foreground, right below the dam, is the hamlet of Rivalta 11- Entrance to Longarone from Pirago, with the villa Scotti on the right and Castellavazzo and Codissago in the distance 12- Longarone railway station in the foreground; further up are the terraces that mark the highest level reached by the flood 13- Via Roma - main road - and the square. Piazza Umberto I° 14- Via Roma twenty years after the disaster 15- In the foreground are Pirago and the road to Zoldo; Longarone church is in the background, with Codissago on the right and Castellavazzo at the top. 16- Close up of the Villa Scotti and the road coming into Longarone from the Zoldo valley. One can also see the Piazza dei Martiri (the square of the Martyrs of resistence). 17- Sports car rally: 'the Gold Cup of the Dolomites' 18- The mayor of Longarone, Guglielmo Celso 19/24- The opening of the Ice Cream Exibition.

Page 51- The first 'Ice Cream Exibition', inaugurated on 13 December 1959, was held in the halls of the cinema next to the town hall. The idea emanated from a group of ice cream makers who worked abroad, people who through their hard work had managed over the years to make their mark on the production and marketing of this product.

Page 32- The event provided an auspicious beginning to an initiative which has led to important developments There is now an accredited qualification for the profession of ice cream making, and high standards for the quality of the product have been brought to the attention of those in the profession as well as throughout Italy. As photographer for the 'Gazzettino' I was given the task of doing all the photography for the show.

Page 33- The late painter from Longarone, Italo Pradella, shown in the foreground in photo no. 25, was (with others) the organizer of various art exhibitions. Some of the photos show the artists at work during a spontaneous show in Via Roma and characteristic settings such as the 'Albergo Posta', the 'Bar Pergolà and the 'Unione Cooperative,' that no longer exist today.

Page 34- I had a particular rapport with Longarone from a professional point of view right from the beginning. From a very young age I knew the people and I never found it difficult to consolidate existing friendships or to create new ones. Some of these were abruptly terminated on the tragic night of 9 October 1963, but the memory of the people and of that time is indelibly imprinted on my mind and remains with me always.

Page 35- My work is dedicated not only to those friends who lost their lives, but also to all of those people who at every level and in every field worked together for the common good. The little town was vibrant and alive, full of energy and initiative. 35- Bepi Zanfron, first on the right, with a group of friends, all of whom died in the catastrophe 37/38- The San Nicola church of the Protti family, and Faè before the disaster 39- The ruins at Faè, towards Longarone, after the Vajont wave had swept through it 40/42- Pictures of a happy time: the marriage of Eugenio Sacchet and Emma Zoldan, celebrated on 25 April 1962 in the little church of Rivalta at Longarone, destroyed during the catastrophe 43/44- The local cyclist, Italo Coletti, passes through the centre of Longarone as he participates in the Piave Cycle Race of 1961 45- Picture of an international football match between Longarone's team and one from north of the Alps 46- Among the spectators was Gino Mazzorana, third from the right, the only survivor of his family, one of the first to be saved during the night 47- The teams line up before the match

48- The U.S. ACLI football team of Longarone. In the front row, from the left: 49- Longarone seen from the street in front of the railway station 50- Colomber bridge, in its time the highest in Italy 51 - View of Therenton bridge, looking down the valley 52- Footbridge over the Vajont gorge, with its warning sign of danger when there are storms 53- Aerial photo of the three bridges: at the bottom the aquaduct; in the distance, the Colomber; at the top the footbridge. 54- The road to Erto with the new bridge over the Vajont 55- 'Therentòn' bridge 56- The footbridge, and in the background the precipice. The bridge was constructed by Giacomo Martinelli and Felice Corona, both specialists in cablework

57/64- Record of the progress made on the construction of the Vajont dam. 63- Detailed view of the construction of the dam, using pre-cast sections 65/68- 4 December 1959 - Santa Barbara. Workers, technicians and managers all at the festival together 69/70- Trial filling of the reservoir after the completion of its construction. In photo no. 69 you can see the Sade and Torno construction villages in the distance.

71 /80- Images showing daily life in Erto and Casso, with

the work of the time, holidays and typical stone houses

Page 49- I had the opportunity to get to know the areas of Erto and Casso and their people on several occasions. I often provided the photography for the procession of Holy Friday. I was also asked to provide photographic evidence for an enquiry into problems the Municipality was experiencing after the first landslide on Mount Toc.

Page 50- The images on this page convey the serenity and tranquillity of daily life in Casso. The Vajont disaster changed things radically and a permanent record remains in the valley in the form of the huge pile of rubble left by the

landslide and the whiteness of the rocks which sheered away from Mount Toc 81- General aerial view of the Vajont in the municipal areas of Erto and Casso; on the right one can see the road that leads from the dam to Pineda. One can also see the houses and mountain chalets below Mount Toc, which collapsed into the lake 82- The reflection of the white peaks of the mountains on the still mirror of the water of the lake is magical, but sends a shiver down the spine when one thinks of what happened later 83- Mount Toc seen from Casso, with the front of the landslide 84- 1961 - This picture conveys the impression of a tranquil life being led on the margins of the dam: women collect wood and carry their heavy loads home 85/87- Landslides from Mount Toc which had already happened before the dam was commissioned, right in front of Erto 86- Photojournalist Bepi Zanfron and journalist Tina Merlin during a site visit to Mount Toc to document a landslide which had already happened and the instability which already existed before the catastrophe 88- The village of Toc on the road to Pineda, which was dragged by the landslide into the lake. Only one house remained intact. 89- View of the lake under the village of San Martino, which was later entirely destroyed by the flood wave. 90- From the left: Attilio Corona, Giovanni De Damiani, and journalists Tina Merlin and Mario Passi 92/93/95- The village of 'I Mulini' below Erto,' abandoned when the reservoir was filled 94- Val de Font, a hamlet in the Erto district, completely destroyed 96/98/100- Lively games played by the children of Erto in the narrow streets covered with snow and ice 97- Journalist Armando Gervasoni, author of several publications on the Vajont, visits Erto 99- View of the main street of Erto, at the beginning of the sixties 101- Typical images of family life: a grandmother watches over the grandchildren while they eat their food on the steps of the house 102/105- Great celebrations on the occasion of confirmation: long lines of boys and girls, about forty in all, from Erto, Casso and surrounding hamlets wait in line 106/108- Work done by the artisan women from the Vajont valley, and their long pilgrimage to sell their products in distant places 109/116- The traditional commemoration of the Passion of Jesus Christ on Holy Friday in Erto. The whole community of the valley of Vajont used to participate, and still do today

The catastrophe

117/118- Photos of the dam and of the reservoir taken several months before the Mount Toc landslide

119/121- 23.00: the first photograph taken of the disaster, a few minutes after the wave of water had swept through Faè. Kneeling on the left is Paolo Bolzan, deputy chief fire officer of Belluno and on his right is marshal Ugo D'Incà. 122- The rubble of Faè exposed to view by a large searchlight brought by the rescue workers 123- Part of the route followed on foot during the night with the help of a small battery-powered torch. The photo was taken in the morning on my return to Belluno 124- A house near Villanova which miraculously remained intact, protected by a spur of rock. While I was passing through to Longarone some survivors called to me for help; as it was impossible for me to do anything. I alerted the team from the fire brigade who were following me 125/127-1 shot these photos during the early hours of the morning on my way back to the town. Only then did I fully realise - as the photos testify - the difficulty of reaching Longarone. During the course of the night I and several others devoted ourselves to the task of helping the survivors that we found in the rubble 128- Aerial photo taken in the morning from the helicopter. One can see the Faesite factory after the wave had hit it, and the road that comes to an abrupt end after a kilometre. This was the point from which I began my long nocturnal walk to Longarone 129- Ado De Col, voluntary fireman, whom I came across in Pirago, as he wandered about looking for his house, saying over and over 'There is nothing here any more. I can't find my family!' 130- Pirago in the morning with its devastated cemetery and the solitary steeple, the only thing left standing amid the devastation 131/132- About one o' clock, in the area of via Roma as I came from Pirago, I heard cries. The rescue workers of Igne and those from Forno di Zoldo were there; there was no equipment at all to help us. The rubble and earth had to be lifted with our bare hands and one simply kept digging until one found the survivor. Emilio Pagogna is holding the lamp while Renato Mazzucco and Bortolo Pellizzari are on their knees 133- Micaela Coletti, saved on the night of the disaster, is visited by Princess Beatrice of Savoy at the Pieve di Cadore hospital 134/136- 2-3 o' clock: the fire brigade, police and volunteers from Agordino, from the Zoldo valley, from Caldore and from the Bellunese area work wherever they hear cries or groans. This is the photographic record of the saving of young Gino Mazzorana, buried under the rubble of the house and found near via Roma. 137- Gino Mazzorana is visited by Princess Beatrice of Savoy 138- Gino Mazzorana and Renzo Scagnet in the Pieve di Cadore hospital some days after the catastrophe. Renzo Scagnet, eight years old, lost his father and his sister. He told a correspondent from the 'Famiglia Cristiana': "I was asleep. Suddenly a great rumble woke me up and I found myself, I have no idea how, in front of the town hall. I thought it was an earthquake." 139- Gino Mazzorana on the thirtieth anniversary of the Vajont disaster Page 72- Micaela Coletti and Gino Mazzorana today recall those terrible moments: Micaela Coletti140- The enormous wave, smashing against the vertical walls beneath Casso, then retreated back down the valley, creating a huge displacement of air which created a whirlpool effect, causing havoc throughout the entire village 141/145- Here I am joined by men with the appropriate tools from the Alpine Brigade of Cadore 141/145- Rescue operations: we began to dig not only as soon as we heard a cry but also if we had the least suspicion that someone might be alive under the rubble 146/153- Photos taken at the first light of day in the area to the north east of Longarone, in that part of the village which had not been destroyed; several survivors were wandering about in the ruins in shock, unable to believe what had happened. In this area voluntary guards were working, coordinated by Paolo De Paoli

Page 76- At the first light of dawn we began the sad task of recovering the bodies, an exercise which took a long time and took us some distance from the scene of the disaster. In some areas, like the one below Pirago, the work was arduous and painstaking as the rubble from the town was all caught up in the narrow Maè gorge. 154- Panoramic view of the area where the railway station used to be, with the remains of the tracks in the foreground 155- In the centre is Giustino Bof, one of the alpine troops who arrived at Longarone with the first rescue workers at 01.30 on 10 October from Tai di Cadore. Hundreds of coffins were required urgently 156- First on the left is Lino Munaro from Irrighe di Chies d'Alpago; on the right is Giacomo Artusi from Introbio (Lecco); both served with the alpine troops of the Cadore brigade. 15 7- A picture showing the complete destruction of Pirago and the solitary steeple standing unscathed among the devastation 160-'Time stood still' 158/159 and 161/164- Divisions of the military hard at work recovering the bodies

165- Another rescue in the early hours of the morning. 166/ - 70- The tragic reality ol dawn 171/172- Views from the helicopter taken at 7.00 on the morning after the tragedy

Page 83- At about 7.00 in the morning I arrived at Belluno airport, where several helicopters had already gathered. The engineer in charge of one of them was Rinaldi, from Rome, and I asked him if he would include me in a flight over the scene of the disaster.

Page 84- Once we had returned to the airport I went back to my studio in via Fantuzzi, where my sister Silvia and colleague Guido Fiabane were waiting for me. The photographs were developed in a few minutes and in response to the requests already received from the 'Gazzettino' and the Associated Press were transmitted immediately via telephoto. 179/181- Pictures showing the enormous amount of material which fell from Mount Toc into the Vajont lake 183- The devastated Piave valley, taken from the helicopter 184- Family members arrive at the scene in the early hours of the morning 186/195- "The rescues, the searching, the desperation, the grief" Page 90- During the early hours of the morning the roads which led to Longarone were blocked to allow rescue vehicles through. The show of solidarity and support was enormous, both from all over Italy and from abroad. It was important to organize the operation well so as not to hamper the work of recovering the bodies and clearing the rubble. 196/205- Men and machines from the Belluno fire brigade at work recovering bodies in the Piave valley, and restoring communications by road 204- The column of vehicles moves slowly along the road which has just been cleared of rubble, carrying the materials so desperately needed for the first rescue operations 206- Father Felice Tomaselli says a blessing over the body of a victim near Villanova 207- Father Fortunate Zalivani, parish priest of Polpet, looks through what remains of the Longarone parish register Page 92- The Belluno church council arranged for priests to be sent to give spiritual assistance and to help with the funerals for the bodies laid out along the banks of the Piave river. Among them were Father Alfonso Zanella, Father Rinaldo Andrich, Father Mario Moretti, and Father Domenico De Toffoli 210- Laying out the tents to house the bodies while they awaited identification. The area later became the cemetery in which the victims were buried 211- Maria Sacchet, in the foreground, proving with other women 212- Casso: the evacuation of the survivors 213- "So many flowers, not very far away from the burial site, for all of those who lost their lives" 215- Emilia Feltrin kneeling next to one of the first graves on which a cross was placed 216- Prof. Joannes Milcinski, who with profound compassion laid out almost all of the bodies of the victims 217- Ceremony in the cemetery of the Victims. In the foreground is Prof. Virgilio Menozzi, the Mourtons, an English couple, and Father Mario Moretti 221 - The layout of the cemetery at Fortogna, with its great wooden cross erected by the fire brigade 224/226- The Piave district of Belluno: evacuation at the first light of dawn after the damage caused by the wave which swept through from the Vajont 229- Recovery of a body on a bend of the Piave river downstream from the Ponte della Vittoria at Belluno 230- Photos of the victims displayed for identification in a room of a provincial civic building in Belluno 231- The transportation of a body, and operations to prevent the spread of disease, all undertaken by the military police 232/234- Images showing the destruction of the village of Codissago, in the municipal district of Castellavazzo 235- The changing of a squad of alpine troops 236- Inhabitants of Casso forced to leave their village, in a helicopter 237/246- The arrival of the emigrants: their eyes were swollen with weeping; they searched for their loved ones and their homes but found only empty spaces 247/250- Activities continued to prevent disease and infection, undertaken by both the Red Cross and the health service. 251- Giovanni De Bona from Longarone who participated in the first survey of the area after the disaster 252- The alpine surveyor Giacomo Artusi given the task by the local military of surveying the destroyed buildings 253- A notice indicating where the Galli technical studio used to stand 255- General Ciglieri, Commander of the Fourth armed corps, coordinates operations 257- Mechanical diggers operating at the site 258- Notice indicating what remained of the 'Postà hotel in Longarone 259- A member of the military police accompanies the families of the victims 260/263- Life continues in the midst of so much desolation 264- An American helicopter flies over the dam to rescue survivors in more remote areas 265/266- The part of Mount Toc which broke away and filled the lake rose high enough to create another mountain 267- Two way radio across the landslide 268- Stortàn, near Erto and Casso. After the wave had destroyed everything it bent this electricity pylon in two 269- Grief and despair 270- Pineda, near Erto 271- The Filippin dei Ditta family from the hamlet of Pineda. The wave lapped against their house 273- Erto and Casso: the work of managing the animals continues despite the landslide 274- Erto cemetery with the crosses of 17 victims; the other bodies were never found 275- Survivors at Cimolais 276- Unloading the items needed for the survivors from Erto and Casso during the first operation 277- Belluno (Villa Montalban): survivors from Erto and Casso 278- Fortogna: feeding the survivors 279/282- General Carlo Ciglieri meets with the mayor, Terenzio Arduini, and other people in authority 283/285- Belluno. The President of the Republic, Antonio Segni, and his wife visit sisters Giovanna and Nives Filippin from the hamlet of Pineda (Erto and Casso)

The reconstruction288- Umberto Zoldan with his grandson, Fulvio Vazza, walks behind Antonietta Zangrando who is with Plinio Vazza, and Angela Zoldan, who is with Giorgio Vazza. They are leaving their home in Muda Maè and going to the home of grandfather Umberto Zoldan in Castellavazzo 290- Carlo Dalla Stella with his daughter 291/294- The children go back to school: there are empty spaces inside the classroom, as well as outside the window. The roll call in the elementary school confirmed this: 157 of their classmates were missing 296- Teacher Gioachino Bratti with some of his pupils who had survived 297- School begins at Cimolais for children from Erto and Casso 298- Giovanni De Damiani, mayor of Erto and Casso, with two of the townsfolk 299/302- Longarone: religious ceremony in the ruins of the church to thank all the armed forces for their work in the disaster zone Page 124 FROM THE OFFICIAL DIARY OF THE REGIMENTS POSTED TO LONGARONE

24.15: The Pieve di Cadore battalion, based at Pieve, was

already at the site.

The Sixth Mountain Artillery Regiment, commanded by Colonel Bruno Gallarotti, comprised 68 officers, 31 petty officers and 1161 artillerymen.

The Seventh Alpine Regiment, commanded by Colonel Massimiliano Brugnara, was already at the site with the commander of the Cadore Brigade, General Umberto Cavanna, before the troops arrived.

The Seventh comprised 58 officers, 29 petty officers and 1119 alpine troops.

The gold medal for bravery in civil life was awarded to the ensigns of the Sixth Mountain and the Seventh Alpine Regiments.

303/304- April 1964. The mayor of Longarone, Terenzio Arduini, and the mayor of Castellavazzo, Rino Zoldan, award honorary citizenship to General Carlo Ciglieri, for his service to humanity during the rescue operation.

305/308- The twinning of the municipalities of Longarone and Bagni di Lucca: the two mayors Tcrenzio Arduini and Mario Lena

309/310- On the right is Giuseppe Samonà, the engineer who drafted the reconstruction plan for the disaster zone. Below is a relief model of the project

311- The prefect of Belluno in discussion with the new first mayor of Longarone (in 1964), Giampiero Protti

312- A tracing showing the new urban layout of Pirago

313- The bridges over the Maè

314- The mayor, Giampiero Protti, discusses the overall plan with the authorities and the townsfolk

315- First geotechnical study of the new railway track

316/317- Reconstruction work on the railway between Padua and Calalzo in the Longarone area

318/320- Reconstruction work on the railway between Padua and Calalzo in the Longarone area

321- Prefabricated buildings at Claut

322- Prefabricated buildings at Pians near Longarone

323- Working on the embankment of the Piave at Longarone

324- Constructing the sewer network in what is now via Roma

325- The Campelli bridge at the foot of the dam, reconstructed to re-establish the link with the villages on the left bank of the Piave

326/328- Reconstruction of the road infrastructure

327- A works site at Rivalta

329/331- Photo of newlyweds Piermarco Tovanella and Maria Sacchet, whose marriage on 30 June 1964 was the first to be celebrated after the catastrophe

Page 133- Maria Sacchet:

"My memory of my wedding day is still vivid and reawakens so many emotions. I am happy that Bepi Zanfron should remind us all of the event, because I always was aware of him being there, energetically involved in the life of our community"

332/334- Visit of cardinal Lercaro for the inauguration of the prefabricated buildings, donated by the diocese of Bologna

335- Ruined statue of the Madonna from Longarone church, found on 10 October 1963 at Fossalta di Piave by the Zamuner brothers, and, perfectly restored, given back to the Longarone community seven months later

336- Procession carrying the statue of the Madonna to the centre of Longarone in 1964

337- At the request of the workers from the Longarone SEP, the statue of the Madonna was displayed on the forecourt in front of the factory

338- The first Vajont exhibition marking the tenth anniversary, held in new special pavilions for the Longarone Fair, finished in 1972. Bepi Zanfron was an exhibitor, shown here with his wife Antonietta and children Luca and Sara.

339/340- The bishop of Belluno and Feltre, Monsignor Gioacchino Muccin, at the opening of the exhibition The bishop asked to be buried in the cemetery of the Victims of Fortogna

341/343- Commemoration of the anniversary of the Vajont disaster in 1979

344/346- Inauguration of the temporary home of the Vajont museum, in the municipality of Longarone

347/348- March 1979: a delegation from the Association of Bellunese Emigrants and survivors is received by Pope John Paul II. The Pope spends some time talking to Bepi Zanfron, originator of the photos in the book "Vajont, memoria di una distruzione"

349/352- 12 July 1987 - John Paul II visits the cemetery for the victims of the Vajont at Fortogna

353/354- 9 October 1983: the President of the Republic, Sandro Pertini, in the cemetery of the Vajont victims

355- March 1979. The President of the Republic, Sandro Pertini, receives the delegation from the Association of Bellunese Emigrants

356- The new Longarone begins to emerge

357- Via Roma

358- Pirago

359- Entrance to Longarone from the Zoldo valley

360- Panoramic view of Longarone towards the new industrial area at the end of the sixties

361- The industrial zone and the first productive activities of the new installations. In the foreground arc the reconstructed houses of the Teza brothers, who lost 72 relatives on the night of 9 October 1963

362/364- Panoramic view of the reconstruction, taken in 1981

365- Church built as a monument to the victims of Vajont, erected on top of the landslide in front of the dam

366- Panoramic view of Erto in 1981

367- Erto and the new Stortàn, constructed in 1981

368- August 1998 - view of Longarone, Codissago and Castellavazzo

369- August 1998 - Longarone and the industrial zone; on the left are Dogna and Provagna

3 70-August 1998: Pirago

371- August 1998: Longarone - via Roma

372- August 1998: Erto/Stortàn with new town hall and church

373-August 1998: view of the Mount Toc landslide

374- August 1998: Erto/Stortàn - main road

375- August 1998: the Vajont gorge with the dam, taken from Pirago valley

376- August 1998: the Vajont dam and the mountain which fell into the lake

377- The mayors from the surrounding areas of Vajont.

378- 7 October 1996. The exhibition of work entitled 'In its time' by Bepi Zanfron is presented at the provincial centre for the promotion of artistic professions in Soverzene

Page 151 - The exhibition was very successful and attracted 3,500 visitors. This exhibition provided the inspiration to collect all my memories together and to publish them in this book

379- Monsignor Pietro Brollo, bishop of Belluno and Feltre, visits the exhibition. On the right are the promoters of the exhibition, Bruno Pittarello, Gianni Burigo and the mayor of Soverzene, Vania Burigo

380- 17 December 1968: trial at L'Aquila (southern-central Italy, 800 km far from Longarone)

381- The defendants

382- Demonstration at Belluno by the inhabitants of the whole Vajont area during the period of the trial at LAquila. The judicial process began on 29 November 1968 and finished on 17 December 1969; on 31 October the sentences were passed by the Court of Appeal; the last act of the drama took place between 15 and 25 March 1971 when the Supreme Court ratified the decision of the previous courts.

383- A demonstration at the Belluno theatre

384- On the left is Arcangelo Mandarino, Procurator of the Republic during the time of the event, and Mario Fabbri, the young investigating judge who proposed the sentences which should be passed on those who were responsible for the

Vajont disaster

385- The tension and anxiety during the time of the trial are reflected on ihe faces of the inhabitants of Erto and Casso who attended the court in LAquila. From the right: Giotta De Bona and Nina De Longo, and behind is Nani De Titta

386/387- In Longarone a group of townsfolk sit in front of the radio awaiting news of the trial in L'Aquila

388/389- Moments during the trial

Four days after the disaster the Italian President, Antonio

Segni, visited the site and called for justice; three years later

the next President of the Republic declared that no effort

would be spared in treating the people who had suffered so

much with the respect and dignity they deserved.v

It was, however, only after four years, three months and eleven days of work that the young investigating judge of the Belluno Tribunal was in a position to charge eleven people with having been responsible for the disaster: technical

managers from Sade, the electricity company subsequently taken over by Enel; officials from the Ministry of Public Works, and university lecturers who had worked as consultants to the project. Two of the accused died before the

investigation was complete. The remaining nine were to be tried, not in Belluno, for «fear of reprisals and unrest», but in L'Aquila, eight hundred kilometres away, a decision taken by the Supreme Court of Venice. This of course made it impossible for those affected by the tragedy to attend.

In the end eight men were charged in court with multiple manslaughter, for having caused a landslide and a flood, aggravated by the foreseeability of the event. One of the engineers committed suicide on the eve of the trial. The public prosecutor recommended twenty one years of imprisonment for the guilty parties, after 149 hearings of evidence and five hours of deliberation.

Nino Alberico Biadene, General Manager of hydraulic construction services for Enel-Sade, Curzio Batini, President of section four of the national body for supervising public works, and Almo Violin, head of the local body for public

works at the time of the disaster, were given six years of imprisonment for manslaughter. Biadene and Batini were acquitted of the charges of causing a landslide and a flood, aggravated by the foreseeability of the event.

The others were acquitted of all charges because what they had done did not constitute crimes: Francesco Sensidoni, General Inspector of the local body for public works; Pietro Frosini, responsible for the testing programme before

the building of the dam; Professor Dino Tonini, head of the planning office at Sade and consultant to Enel, and Roberto Marin, General Manager of Enel-Sade.

This outcome was unacceptable to the people of Longarone, and led to the second trial which began on 26 July 1970 and concluded on 3 October of that year. The Court of Appeal at L'Aquila found Biadene and Sensidoni guilty of all crimes

and sentenced Biadene to six years imprisonment and Sensidoni to four years and six months, sentences which were then reduced as a result of mitigating circumstances. Violin and Frosini were acquitted for lack of evidence; Marin and

Tonini were released because what they had done did not constitute a crime, and Ghetti was acquitted of any involvement.

The case then returned to the Supreme Court who reached their conclusion on 25 March 1971 after ten days. The charges relating to having caused a landslide and a flood were commuted into one crime of involuntary manslaughter, while the issue of the foreseeability of the event was placed on one side. Biadene and Sensidoni had their sentences reduced to five years and three years and eight months respectively, which after a government amnesty shrank to two years for Biadene and eight months for Sensidoni. They did not therefore serve even half a day for each of the two thousand crosses on the mountainside.

The civil proceedings were even more tortuous. Those who had lost children were offered compensation of one million five hundred thousand lire per child; those who had lost more distant relatives were offered much less [please read this part of the story]. Some of the survivors accepted these terms, while others, aggrieved,

tried to sue for compensation for their pain and deprivation, all of which could have been avoided. The judges were indecisive on whether compensation could be paid on this basis, settling for a fudge which by implication made the perpetrators of the crime guilty of murder.

From a legal point of view, there was one victory: this was the first time that the Supreme Court had confirmed the liability of employers in criminal law for the safety of their employees, when they undertook activities which carried life-threatening risks. The whole case, however, provides sobering evidence of how the surveys and reports prepared by the best of our technicians and scientists can be manipulated in order to serve other more powerful interests ("a State whitin the State", n.d.r.).

(God bless you, Bepi !!)

Ritagli di giornali, libere opinioni, ricerche storiche, testi e impaginazione di: Tiziano Dal Farra

|

|

|

|

|